REPORT OF THE MEDICAL TEAM ON NANDIGRAM INCIDENT OF 14.03.2007

After the incident of firing by the police at Nandigram on 14.3.2007, report of large-scale injuries and ailments arising out of and as a consequence of the said incident had reached the media. Some doctors and health workers decided to visit the affected area to render the very urgent medical help to the people affected by the incident.

A team of doctors (Medical Service Centre, Kolkata) visited several affected areas of Nandigram on 17.3.2007 and came out with a report, which was reported in the press.

OUR FIRST VISIT (18.03.2007)

On 18.3.2007, a team comprising of six physicians (including 2 female physicians), three junior doctors, sisters, medical students and health-workers, organised by public-spirited organizations working on health, i.e., SRAMAJIBI SWASTHA UDYOG, PEOPLES’ HEALTH and JANASWASTHA SWADIKAR MANCHA, visited some of the affected areas of Nandigram to render medical help to the affected people.

The Medical Team found that more severely injured patients had mostly been taken to the hospital and persons who were critically injured had been transferred to Tomluk Hospital (District Hospital) and SSKM Hospital / RGKar MCH of Kolkata. But they found that a very large population, predominantly women, were suffering from blunt trauma injuries, very often multiple, and had not received any medical help. The same is true also for a very large number of people, suffering from eye-problems ( headache, watering, photophobia, burning sensation, dimness of vision etc.) even 4 days after the tear-gas exposure on 14.3.2007. People were also suffering from mental trauma, though unfortunately the medical team did not have a psychiatrist or a psychologist who could have professionally assessed the actual extent of the trauma. The medical team treated 129 patients and had the opportunity to talk to about 300 victims, who described the unprovoked and brutal attack on unarmed assembly of villagers, including a large number of women and children, which continued even after people had dispersed and was trying to flee from the scene. The women also described with horrid details of sexual assaults on them. Attackers, they said, included a large number of persons in police uniform but with chappals on.

The Medical Team had also found that many could not return to their home and resume their normal activities. Camps were organized by the local people to provide food for these affected people. These camps were found to be suffering from an acute shortage of provisions required to run the kitchen (the medical team bought a day’s provision to one camp).

2ND VISIT (21.03.2007)

The next visit took place on 21.3.2007. It was a general relief cum medical relief team, consisting of two physicians and four health workers. There was plan for documenting the trauma of the victims, though due to shortage of time, addition burden of general relief work, the number of patients treated and documented was limited to only 30 in three different places. General relief and provisions worth Rs 15, 790 were provided to four different relief camps in the affected areas.

3RD VISIT (24-24 March, 2007)

The third visit was on 24-25th March, 2007. From the experience of two previous visits by the medical team, it was decided that the team should stay overnight in the affected area to render more intensive and extensive medical assistance, and that it would concentrate on medical relief only.

This time the team comprised of eight doctors, including two female doctors and one orthopaedic surgeon, one sister and seven health workers. They organized 4 medical camps, in Southkhali (24.3.2007), Sonachura High School (25.3.2007), Kalicharanpur Primary School ( 25.3.2007) and

Dakshin Jalpai, Bhangabera (25.3.2007). It may be mentioned here that one eye relief camp was organized concurrently in Sonachura High School on 25.3.2007 by ARGUS COMMUNITY EYE SERVICES.

A brief description of various patients on 18.3.2007. The documentation quality was not upto the mark on this day as the medical team was overwhelmed by the extent and the magnitude of the problem.

Camp: Sonachura

Date: 18.3.2007

Total cases seen: 129

Female : more than 80% .

Eye problems 40%

Direct hit by the police 45%

Other Musculo-skeletal injury 5%

Wound 5%

A brief description of various types of patients seen on 21.3.2007 is as follows:

Camp: Sonachura and Garchakraberia

Date: 21.3.2007

Total cases seen: 30

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 25

Male 18 (72%)

Female 7 (28%)

Child 3

Eye problems 16 (64%)

Direct hit by the police 6 (24%)

Other Musculo-skeletal injury 4 (16%)

Mental problem 3 (12%)

Thigh Injury 1

Headache 1

Back pain 1

Blunt Injury 4 (16%)

Ear problem 2 (8%)

Wound 3 (12%)

Haematoma 1

A brief description of various types of patients seen on 24/25.3.2007 is as follows (details in Annexure 1):

Camps: Soudkhali, Kalicharanpur, Dakshin Jalpai, Sonachura

Date: 24.3.2007 and 25.3.2007

Total cases seen: 261

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 230

Male 83 (36%)

Female 147 (64%)

Child 9 (4%)

Hindu (mostly SC) 222

Muslim 8

Eye problems 135 (58.6%)

Direct hit by the police 54 (23.4%)

Other musculo-skeletal injury 41 (17.8%)

Multiple Injury 27 (11.7%)

Bullet Injury 4

Ear injury 2 (children)

Fracture 1

Spinal Injury 1

Mental trauma 28 (12.1%)

· 70% to 80% of the patients of all camps had eye problems since 14.3.2007, but in Sonachura camp these patients attended cocurrently running eye camp, hence the average shows a lower figure

· The details of different camps has been shown in Annexure I.

· The doctors in the team (except those at Sonachura camp) had no training in properly assessing post traumatic stress, hence this condition may be found to be under reported particularly in the three other camps.

Eye Camp: Sonachura

Date: 25.3.2007

Organised by: ARGUS COMMUNITY EYE SERVICES

Total cases seen: 155

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 114

Male 55 (48.2%)

Female 55 (48.2%)

Child 4

Hindu (mostly SC) ALL

Muslim Nil

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS:

1. It was seen from the TV clips that many persons were shot at the chest, abdomen and even in their heads, though when dispersing a mob, the police is to “use as little force and do as little injury to person and property as may be consistent with dispersing the assembly, arresting and detaining such persons”. ( Section 130, CrPc).

2. The medical team also saw other cases of bullet injuries at face level in the village.

3. The number of victims was found to be very large and included a large number of women and children also.

4. The lathi charge was extensive, it was inflicted even on women who had already fled from the place of assembly and was hiding in nearby houses and bushes in and around the place. This lathi charge was severe, producing multiple blunt injuries with bruises which was evident on medical examination even on 4/7/11/12 days after the event. These injuries included fracture, spine injury, chest injury etc. Injury marks were mostly found on the upper part of the boby upwards. It may be mentioned here that when the medical team had reached the scene, the people with major injuries had already been taken to various hospitals.

5. Many people suffered from the musculo-skeletal injuries including fall etc., as they were trying to escape the scene and police was persistently chasing them.

6. Many persons were injured due to beating by the police while they were trying to rescue the injured persons and the children.

7. Many women complained of sexual assault. They were also found to bear injury marks on their breasts, abdomen and private part. However, lack of privacy and other infrastructure prevented the medical team from proper physical examination and even thorough history taking.

8. A very large number of affected people, predominantly women, were found to be suffering from eye problems (burning sensation, watering, phototophobia, headache, dimness of vision etc), persisting even 11 days after exposure to tear gas. So much so that every camp attended to 70-80 percent of patient suffering from eye problems related to tear gas exposure. It may be noted that the people were aware that there may be tear gas attack, they knew that in case of tear gas attack they were to wash the eyes with copious amount of water, and they followed this instruction. Some persons also had injury in eye and other parts of the body from tear gas shell explosion, burn injury from contact of tear gas shell, history of breathlessness from close exposure to tear gas.

9. Thus it appears to the medical team that the gas used against the people may not be the usual tear gas ordinarily used to disperse the mob, but something unusual having more permanent and serious effects. The medical team urges a serious investigation into this matter.

10. It was found that although most of the severely wounded people were transferred to hospitals, a few seriously wounded persons, including a nine year old boy suffering from supracondylar fracture of arm, a spinal injury patient etc., practically received no medical attention. Also, many people, who attended Nandigram Hospital, did not receive medicines due to shortage of required medicine and many patients could not be examined and investigated properly due to lack of infrastructure there. Patients suffering from eye problems received almost no medical treatment. It may be noted here that Nadigram Hospital (BPHC) may be called a glorified primary health center and is not equipped to deal with so many serious injury and other cases. It was learnt that this Hospital did not receive much additional support even after the incident.

11. Many patients were found to be suffering from mental trauma with symptoms of sleeplessness, anorexia, anxiety and fear. Many women saw people, even children being killed, wounded people snatched. They were in fear of repeat of attack, anxiety for the safety of near and dear ones, and particularly about sexual assault of young daughters. But unfortunately the medical team did have trained human resource to properly assess situation, so the number of patients suffering from mental trauma mentioned here would be an understatement of the actual state of affairs. However, a team of psychiatrists, psychologists and other mental health workers has already organized a camp in Sonachura on 31.3.2007. Their reports will be published soon.

12. An interesting observation was that very few patients came to the medical camp for ailments unrelated to the incidence of 14.3.2007 and those who came for injuries etc also mainly reported the injuries only and generally had no other medical complain.

13. The team of doctors also conducted a training camp for local volunteers so that if any untoward incident takes place again, these volunteers would be in a position to render rudimentary patient care (containment of bleeding, removing the patients observing proper protocol, wound dressing and things like that). 22 volunteers from different parts of the area covering almost the entire affected area were trained and 10 emergency kit with a couple of manuals in Bengali language were distributed among them.

14. On the two previous visits the Team attended to 169 patients. Though those two visits were not very well documented, it can be said that the general observation was basically the same.

15. Members of the Team also visited Nandigram Hospital, Tamluk Hospital

(Annexure II) and SSKM Hospital (Annexure III).

Dated 3.4.2007

ANNEXURE –I

Camp: Southkhali

Date: 24.3.2007

Total cases seen: 80

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 72

Male 16 (22%)

Female 56 (78%)

Child 1

Hindu (mostly SC) 64

Muslim 8

Eye problems 55 (76.4%)

Direct hit by the police 13 (18%)

Other Musculo-skeletal injury 7

Multiple Injury 10 (13.9%)

Fracture 1

Bleeding P/V since 14.3.2007 1

Injury to private parts (female) 1

Mental Trauma 6 (8.3%)

Camp: Dakshin Jalpai, bhangabera

Date: 25.3.2007

Total cases seen: 54

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 46

Male 24 (52.2%)

Female 22 (47.8%)

Child 1

Hindu (mostly SC) ALL

Muslim Nil

Eye problems 33 (71.7%)

Direct hit by the police 8 (17.4%)

Other musculo-skeletal injury 17 (37%)

Multiple Injury 1

Spinal Injury 1

Sexual assault on 14.3.2007 1

Mental Trauma 6 (8.3%)

Camp: Kalicharanpur

Date: 25.3.2007

Total cases seen: 56

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 53

Male 8 (15%)

Female 45 (85%)

Hindu (mostly SC) ALL

Muslim Nil

Eye problems 43 (81.7%)

Direct hit by the police 13 (24%)

Other musculo-skeletal injury 7 (13%)

Multiple Injury 4

Bullet Injury 2

Sexual assault on 14.3.2007 3

Mental Trauma 4 (7.5%)

Camp: Sonachura

Date: 25.3.2007

Total cases seen: 82

Cases directly related to the incident of 14.3.2007 59

Male 35 (59.3%)

Female 24 (40.7%)

Child 7 (11.8%)

Hindu (mostly SC) ALL

Muslim Nil

Eye problems 5*

Direct hit by the police 19 (34%)

Other musculo-skeletal injury 29 (17%)

Multiple Injury 13 (20.3%)

Bullet & Splinter Injury 2

Ear injury 2 (children)

Mental Trauma 13 (20.3%)

Others 2

· A concurrent eye clinic was running at the same place

ANNEXURE- II

Patients In Tamluk Hospital

Some of the members of the team paid a visit to the Tamluk State Hospital on 1.4.2007, where a large number of injured patients of the said incident

(on 14.3.2007) were admitted. Most of the patients were admitted in this Hospital on or after 16.3.2007; some of them had been referred to by the

Nandigram Hospital, either due to lack of infrastructure, or because of the seriousness of injury. The team talked with the patients, had discussion with the attending physicians. Some of the salient features that the members of the medical team came to know may be summarised as follows:

1. The patients admitted in Tamluk Hospital Hospital had major trauma. They has bullet injury, fracture, multiple fractures, Head Injury, amputation, eye injury, chest injury, breathing problems, history of sexual assault etc. Some are immobilised in POP casing and castings, many had operations, one was on Intravenous drip even 17 days after the incidence.

2. Almost all of those who had been admitted to this Hospital (Tamluk State Hospital) on or after 16.3.2007, complained of various degrees of eye problems ranging from watering, burning sensation, headache, photophobia and dimness of vision. As on 31.3.2007, only about half of the patients have more or less recovered from the problems on treatment with antibiotic and steroid eye drops along with lubricating and analgesic eye drops, but in the other half the problem is still persisting.

3. On 16th March 37 patients were admitted from various parts of the affected area, who had major injuries and injuries inflicted by bullets, tear gas shells, police lathi charge, rubber bullets etc. These patients were initially treated for these grave conditions, but when they recovered a little, they also complained of similar eye problems.

4. 18 patients were transferred from Tamluk Hospital to SSKM Hospital, Kolkata between 17th and 31st March, 2007. 15 of them had bullet injury

and one had Head injury from lathi charge. 7 of bullet injury patient were female and 8 male.

5. Between 16.03.2007 to 1.04 2007 seventy-four patients have been treated for severe injury and conditions in Tamluk Hospital. Of them, 28 were

male and 46 female.

Patients admitted in ‘Nandigram Ward’ of Tamluk Hospital (Female)

1. Satyabala Mondal w/o Anadi Vill.Soudkhali Headache

2. Arati Maity w/o Tapan Vill. Kalicharanpur Headache, Eye complains

3. Kabita Das Adhikari w/o Subal Vill.Gokulnagar # Rt patella, Lt wrist

4. Renuka Kar w/o Shyamapada Vill. Kalicharanpur pain all over due to lathi charge

5. Bidyut Basanta 48/F w/o Mahadev # Lt forearm, Rt finger, eye complaints

6. Radharani Pakhira 45/Fw/o Kishan Vill 7 no Jalpai eye complains

7. Salma Bibi w/o Fakrul Vill.Garchakraberi Bleeding p/v

8. Anima Jana 32/F w/o Prasanta Vill.Soudkhali Eye pain, dimness of vision

9. Sovarani Singh w/o Gorachand Vill.Soudkhali Blunt Injury waist, thigh

10. Paribala dhapar w/o Ranjit Vill.Soudkhali Eye pain, Headache

11. Sandhyarani Sinha 25/Fw/o Ramkrishna Vill.Soudkhali Eye complains, Headache

12. Chhabirani Dhapar w/o Badal Vill.Soudkhali Eye complains, Headache

13. Angurbala Dolui w/o (late) Makhan Vill.Soudkhali Eye complains, dimness of vision

14. Sandhya Dhapar w/o Paresh Vill.Soudkhali Eye complains, Headache

15. Sulekha Das w/o Pravanjan Vill. Kalicharanpur # Lt leg

16. Sailabala Das 48/F w/o Nandalal Vill.Gokulnagar Chest pain, Breathlessness, eye complains

17. Shyamali Mahato45/F w/o (late)Gobinda Vill. Sonachura Head Injury, Bullet injury

18. Radharani Ari 45/F w/o Pratap Vill.Gokulnagar Headache, Eye complains

19. Anubha Khanda 48/F w/o Rasbehari Vill. Sonachura Bullet Injury knee, Eye Complains

20. Kalpana Jana 40/F w/o Nandalal Vill. Kalicharanpur Eye complains

21. Sankari Gol 47/F w/o Manoranjan Vill. Sonachura # tibia, multiple injury head, eye complains

22. Shyamali Mahato w/o (late) Gobinda Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury head

II. Patients admitted in ‘Nandigram Ward’ of Tamluk Hospital (male)

1 Gopal Das s/o Mrityunjoy Vill. Sonachura bullet injury, shoulder

2 Niranjan Das 38/M s/o (late) Radhakrishna Vill. Sonachura Chest Pain

3 Lakshmikanta Gayen s/o Ramhari Vill. Sonachura subconj Hmge, # finger, loss of teeth

4 Subodh Das 45/M s/o Gangadhar vill.Gangra Bullet injury finger

5 Asok Mondal s/o Jagadish Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury, finger amputed,

6 Srimanta Mondal s/o Joydev vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury, thigh

7 Gopal Majhi s/o Santosh vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury, arm

8 Sk.Fasi Alam s/o Abdul Vill 7 no Jalpai Bullet injury, finger

9 Abinash Mondal s/o Gorachand vill.Gangra Pain Back, eye problems

10.Madan Mondal s/o Ramhari Vill.Soudkhali Headache, Eye complains

11. Ramkrishna Maiti 33/Ms/o Chintamani Vill 7 no Jalpai Shoulder Dislocation, Head injury

III. Cases transferred to SSKM Hospital,Kolkata (female)

1. Haimabati Halder Vill. Gangra Bullet injury

2. Kanchan Mal w/o Sripati Vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury

3. Tapasi Das w/o Sambhu Vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury

4. Banasri Acharya w/o Chandan vill. Badkeshabpur Bullet injury

5. Swarnamoyee Das w/o Gopal Vill. Berachak Bullet injury

6. Bhabani Giri w/o Hitendralal Vill. Kalicharanpur Bullet injury

7. Anjali Das w/o Mrityunjoy Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury

8. Gourirani Das w/o Chittaranjan Vill. Kalicharanpur Bullet injury

9. Purnima Mondal w/o Gobardhan Vill. Gokulnagar blunt Injury

IV. Cases transferred to SSKM Hospital,Kolkata (male)

1. Rasbehari Khanda s/o (late) Kumar Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury

2. Abhijit Samanta Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury

3. Swapan Giri Vill. Sonachura Bullet injury

4. Salil Das Adhikari s/o Bhupati Vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury

5. Prithwish Das s/o Purnachandra Vill. Gangra Bullet injury

6. Abhijit Giri s/o Pratap Vill. Kalicharanpur Bullet injury

7. Parikshit Maiti s/o Abinash Vill. Kalicharanpur Bullet injury

8. Mani Rana Vill. Gokulnagar Bullet injury

9. Saddam Hossain Vill 7 no Jalpai Bullet injury

Some Highlights

1. Radharani Ari. Found unconscious (and without clothes) in a bush 2 days after the incidence. Complained of pain in whole body and particularly in

private parts after regaining consciousness. According to her, 3 male police took her to a bush and were beating her, when she lost consciousness.

2. Kabita Adhikari. Fracture Rt patella and Lt wrist. According to her, she was in Anadi Mal’s home on 14th March, when male police dragged her out and beaten her severly.

3. Sankari Gol. Severely beaten by male police, admitted with Rt leg fracture and multiple injury with stitches on head.

4. Sovarani Sinha. According to her, a child was snatched away and killed before her eyes.

5..Anubha Khanda. Admitted with bubber bullet in knee, admitted and operated on 14th March. Her husband Rasbehari Khanda has been transferred

to SSKM Hospital, Kolkata in very serious condition, now in intensive care unit.

ANNEXURE III

List of Patients Injured in Nandigram, now Admitted in SSKM Hospital :

Sl no. Name Age/sex Village Injury Remarks

1 Parikshit MaityS/o (Late) Abinash 55/M Kalicharanpur Bullet Injury abdomen

2 Avijit SamsntaS/o Subimal 33/M Sonachura Bullet Injury Chest, Opeation done on 28.03.2007

3 Avijit GiriS/o Pratap Chandra 22/M Kalicharanpur Bullet Injury Rt hand, Charra Injury Abdomen

4 Pritish DasS/o (Late) Purnachandra 29/M Gangra Bullet Injury Head, Back

5 Swapan GiriS/o Gobinda 21/M Sonachura Bullet Injury Rt Hand

6 Mani RanaS/o (Late) Beni 18/M Gokulnagar Bullet Injury Rt Thigh, Operation done on 27.03.2007

7 Salil Das AdhikariS/o (Late) Bhupaticharan 35/M Gokulnagar Bullet Injury between Lt eye and nose

8 Anjali DasW/o Mrityunjoy 50/F Sonachura Injury, beaten by police and CPI(M) cadres

9 Swarnamoyee DasW/o Gopal Das 32/F Gokulnagar Bullet Injury Lt Elbow

10 Kanchan MalW/o Swapan 45/F Gokulnagar 4 Bullet injuries in Breasts and 3 in Lt Hand, Operated twice.Injured while trying to rescue an injured person

11 Purnima MondalW/o Pipu /F Gokulnagar Heavily beaten up by CPI(M) cadres on 24.3.07 at Tekhali. Admitted on 25.3.07 via Tamluk Sadar Hospital

12 Gouri Rani DasW/o Chittaranjan 40/F Kalicharanpur Injury from Tear Gas Shell, Transferred to ICU

13 Bhawani GiriW/o Jiten 40/F Kalicharanpur Bullet Injury Lt Chest

14 Rasbehari KharaS/o(Late) Kumar 45/M Sonachura Bullet Injury Abdomen

15 Saddam HossainS/o Serajul Islam 18/M Barjamtala7 no Jalpai Bullet Injury Rt Eyebrow. A student of class IX. Now almost blind

16 Tapasi DasW/o Sambhu 32/F Gokulnagar Bullet Injury Hip

17 Manju Mal Discharged on 29.3.07

18 Banashree Acharya Discharged on 26.3.07

19 Haimabati Halder

ANNEXURE- IV

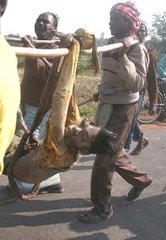

Photographic evidences of some of the persons injured in the incidence of 14.3.2007

1. Minhazur s/o Noorjahan Age 8 years, Villege Soudhkhali. Was with his mother in the Namaz ceremony that was held at Bhangabera. When police

resorted to lathicharge, he received 4 blows in left elbow, resulting in a supracondylar fracture. These two photographs show the extent and seriousness of the injury before (1A) the team had rendered medical care and after (1B).

2. Saraswati Das, w/o late Kalipada Das, Villege Gangra F 40. Was in the puja ceremony at Bhangabera. When the tear gas shelling started, she

started running for shelter. A shell exploded close to her. She had a burning sensation. The police chased her out and she received two mighty blows in her right leg. The police had beaten her up when she fell down in the ground. The photograph ( 2) shows the wound because of the blows that she received from the police. It may be mentioned here that even after a week of the said incident, she did not receive any medical attention.

3. Tapasi Das, w/o of Late Ratan Das, who was killed during the firing on 14.3.2007, Villege Gangra, Sonachura, F 24. Widowed with two small kids.

Lost all tranquility, stopped speaking. Accute Stress-induced trauma.

4. Sonali Das, W/o Pabitra Das, F 26, Villege Sonachura. Was near to the puja ceremony site. When firing started she started running and was

engulfed by the tear gas fumes. She lost direction and was beaten up by the police at the left elbow. Did not receive any medical help even after a week.

Previous Report

On 18th March 2007, 4 days after the massacre at Nandigram a medical team comprising of six doctors ( including two female doctors ),three junior doctors ( house staff of Medical College, Kolkata ),3 sisters and two health workers went to the affected areas to provide medical service to the victims of police atrocities. Three voluntary organizations (working in the field of health), namely Shramajibi Swasthya Udyog, Peoples’ Health & Janaswasthya Swadhikar Manch organized the medical camp.

The members first went to Nandigram Hospital (actually a glorified health center, with minimum infrastructural facilities), talked to four women (one of them accompanied by a very young child), who were admitted in the wards. Then the team went to Sonachura and Adhikaripara (Gokulnagar Area) and gave treatment to 129 affected persons. They also talked to above 300 villagers. Locals like Sri Prodyot Maity, Sri Buddhadeb Mondal, Sri Subhendu Karan; Sri Nishikanto Mondal (a leader of the committee for prevention of land acquisition) helped the team much and guided it to the worst affected areas.

From the dialogue with the villagers that included many eye- witnesses of the ghastly incident, a horrifying story of torture, murder, molestation, rape and killing of children gradually unfolded—which in our view is a planned genocide and barbaric large scale sexual crimes committed upon innocent people. The description, appear to us nightmarish and in spite of our long standing association with medical profession ranging from some years to few decades—some of us felt mentally sick.

Ours was not a fact finding team. These are collateral information that we have gathered. But we feel that it is our duty to communicate this monstrous and sinister incidence that stands singular and in isolation (the comment made by Winston Churchill in the British Parliament after Jalianwala Bag massacre) to the world outside Nandigram. Rest is up to the readers to believe or to reject.

We took some photographs also, which are in our custody and may be circulated in future. With the prelude, let us divulge what the locals said on that day to us.

The local people irrespective of their villages, ages and sex told us the incidences as summarized below—

A.

A lot of people (ranging up to few hundreds) are still missing. It is not that all of them are killed. Some have fled away but the number of casualties are many fold of the officially declared number of 14.In Sonachura alone 50-60 people are untraceable.

No comprehensive list of the missing person is available till date. Firstly, because they are still shell socked and dumb in horror and pain. There is no one to take such initiative for door to door survey (like a census) in the vast stretch of area. Secondly, due to absolute lack of faith in administration/ police and to avoid harassment (including arrest), no one has formally lodged a missing diary either.

B.

The locals say that many families have been torn apart as occurred after Tsunami. One house has got only two children with the father battling for life at hospital and in the other missing. Many have lost their parents, children or beloved who are not included in the lists stain and hospitalized persons. The villagers say that some of them, who ran away, may come back after some time and a proper account of the loss can be taken only after that.

C.

Many small children of the K.G. school are missing in Bhangabera (another badly hit village). The villagers say that during the commotion they were released from the school. Many of them had been butchered by the attackers. Their throats were slit or heads chopped off, put in gunny bags, loaded in trucks and transported to unknown destinations. The locals feel that either the bodies had been burnt in brick-kilns, thrown to Haldi River / Bay of Bengal (not very far off) by tying with stones in fishing nets or dumped in marshy land or jungles. It may so happen that the bodies to the ditches and the overlying roads repaired. Some people said that they have either witnessed themselves or heard from other that the legs of a small child were torn apart. A breast-fed baby was reportedly thrown to a pond.

D.

It is the general perception that the trucks carrying the materials for road repair were extensively used to transport dead bodies during 48 hours subsequent to the attack, when neither the media nor the ‘opponents’ from outside the ‘action area’ were allowed to infiltrate.

It may be mentioned here that news was published in the Bengali Daily Statesman on March 19 that a truck loaded with bullet-ridden bodies covered with tarpaulin was taken to the Haldia State General Hospital at Durgachak past midnight. The hospital superintendent was asked to keep the bodies of the victims of a so called road traffic accident in the hospital morgue ‘temporarily’. The superintendent refused to oblige and was threatened with dire consequences. By refusing to oblige he drew the wrath of almighty Sri Laxman Seth, the M.P. of Haldia.

E.

Many persons were chased and hacked or smashed to death by sharp or blunt weapons. Their bodies were carried away to abolish evidence as it occurred in Chhoto Angaria of West Midnapur, where bodies of eleven murdered persons could never be traced. The local wanted to show us a portion of a road at Bhangabera which was still thickly smeared with blood and even with soft brain matter. They said that the CPI (M) goons tried to wash away the blood stains throughout the night by lighting halogen lamps with generators but failed. The site has been visited by the CBI officials.

F.

Stories of rape and molestation are widespread. The locals say in the aftermath of the attack, the hard core criminals hired by the CPI (M) took advantage of the situation in a full swing. The male members of the families ran away. The criminals attacked, molested and even gang raped the hapless farmers’ wives and daughters even in the broad daylight. They did not spare the aged also. One lady in her fifteen bears deep cut marks on chest by sharp weapons and other marks of molestation. Villagers tell that a number of teenage girls or young unmarried women have been abducted without trace. The locals believe that were taken to the house of Naba Samanta ( a CPI(M) party member cum muscleman and brother of the local tyrant Sankar Samanta who was burnt to death after the fired on the mob from his house ),gang raped and slaughtered. Villagers insisted us to visit the place to see blood stained female undergarments, sarees,broken bangles etc.still lying there. But we could not go, partly due to the shortage of time and partly due to the fear. We saw a young girl (14 to 16 years) is moving all along the team with a small packet in her hand. On enquiry, it was known that many young girls are afraid of staying back home alone lest they are attacked and tortured by police or cadres of CPI(M).They were loitering in public places in the village. At night, many women are hiding in the bushes and not staying at the thatched houses which can be attacked any time. Men are also sitting or lying sleeplessly on the paddy field for last 3-4days (since the attack).The apprehension of quick and organized removal of dead bodies is overwhelming. At Sonachur, an eyewitness lady told that after the firing a number of persons (including children) were jolting in pain and screaming for help on the bank of the pond of Naba Samanta .They were wanting water. The pond turned red. The assistance could reach them on the face of attack. The attackers killed some by them by stones or by bamboo sticks. After two hours, when the villagers could approach the spot, no one was left out. This is a big puzzle. The villagers believe that the bodies and half dead are carried away.

Who fired on them?

Men in uniform, but some of them with ‘chappals’ on their feet. It was revealed subsequently that the CPI (M) procured some 250-300 sets of police uniform from the local ‘Sunny Tailors’ a month back. The villagers concluded that the uniform clad goons accompanied the police force on that day.

The injury marks:

There were all sorts of injuries e.g.

1. Bullet injuries—most of the injured either died or were transferred to hospitals.

2. Injuries on heads caused by blunt weapons.

3. Injury on the forehead of a woman in her seventies caused by some sharp weapon.

4. Extensive and barbaric lathi-charge marks on the whole bodies of women and men. Even after 4 days the parts were red, hot, swollen and very painful. Some of them may have fractures but x-rays could not be done. Some of them were still unable to move from beds.

About three-fourth of the victims are children and women. Interestingly the preferred part of the woman body for such attack was below the umbilicus and above the knees. A rod was forcefully driven to the private part of a lady.

When some persons attacked a lady, her husband resisted. The attackers threatened to kill their small child. The husband ran away with the small child and the lady was molested.

We met two victims who requested to remain anonymous lest they were not accepted by the society. One of them came to her father’s house and was molested on the black day. Villagers said that there were more victims who were too shy to depose before us.

5. Many patients (including children) complained of eye problems—blurring of vision, eye pain and burning sensation in eyes following exposure to tear gas. A number of elderly patients complained of loss of vision.

Name of the attackers

Police and CPI (M) henchmen like Naba Samanta, Jaidev Paik, Anup Mondal, Badal Mondal etc. allegedly led the attack.

Current situation

Still there is tension in the locality and enough provocation by the CPI (M) men from the other side of the canal (Khejuri side), they bring out armed processions with slogans like ‘Those who want to destabilize industrialization will not be spared’. We saw such a long procession ourselves.

There are spates of bombing across the canal throughout the night. People spend sleepless nights. The assurance of peace appears hollow to them and they believe that CPI (M) is taking a breathing time only to bounce back with more force after a month or two.

There is no faith in police as the criminals are hiding in the police camps at times. The police camps are the source of constant fear to the villagers and they want removal of the camps. They are not even ready to allow any government medical team to enter the villages. A fear psychosis looms large in the whole area.

Since agriculture and other economic activities are at stake, there is crisis of food in many houses. Moreover the villagers can not go freely to the market places as police and CPI (M) musclemen often abduct persons moving alone or in small groups.

What we felt

The loss of life is huge, the physical injuries widespread, the psychological trauma unthinkable. The women and the children are the worst affected. In the days to come, many of them are likely to suffer from various psychiatric disorders.

But the morale is still high. Still they are not ready to part with even an inch of their ancestral land, which they consider like their mother. They declare that even further blood shed will not be able crush their movement.

Many people spontaneously came out and spoke to us. They said repeatedly that since they were almost living in ghettos, they were unaware of the impact of their movement on the outer society. There are needs of medicines, food and clothes. But most badly needed is the healing touch of the civil society.

Another team visited Nandigram on March 24-25. They have examined 240 vicitms, treated them and documented their injuries. They also trained activists in First Aid. Their report will be sent to you soon.

April 2nd, 2007 at 11:16 am

Saroj’s writeup, though coherent and to the point, defocuses his own correct logic by utilising borrowed notions from ideological populism (”people” etc) and post-modernism. Statements like the following, which are abundant in the note, are in fact his own non-inclination to put things in a class perspective, of which he accuses others:

“Reports from Nandigram seem to suggest that people are not just fighting to keep their land and their present means of livelihood but they are also destroying the relations of power that tied them to capital and the state”.

Who are these people? Are all of them seeking to destroy “the relations of power that tied them to capital and the state”? If we understand the West Bengal situation in a political economic and historical perspective, we will have to disaggregate this “people”, since there isn’t any homogeneous connection of “the people” to “capital and the state” today (at least not in the societies like West Bengal, which are well integrated with the mainstream Indian political economy). There must be an attempt to understand and ‘deconstruct’ the present agitations in terms of class differentiation that has perpetuated in rural Bengal under the CPIM rule. Various class interests might have integrated temporarily in the present agitations, but this is not sustainable, any Marxist intervention should start with disaggregating them and strategising on this basis. Any “people” vs capital type logic is bound to lead to the deadend of the status quoist power politics which nurtures itself by such homogenised dichotomisations, “civil society” vs the state etc.

In my view, Saroj is correct when he criticises “rights groups” “social movement” for their legalist and ‘right’-ist discourses, but he utilised similar reified notions of people, outside, secession etc. Like the former, he too thinks in terms of “middle class” “joining the people”. The only difference is that the former suffers from the middle class impotency, while Saroj seems to represent his energy from the middle class self-hatred which integrates him with the Maoists.

May 31st, 2007 at 7:12 am

Here’s an article by Sunanda Sanyal published in The Statesman (Kolkata) of 31 May 2007.

The pus focus of a deep festering abscess

by Sunanda Sanyal

What’s absolutely the limit to violence on their women that males in Bengal can bear with? What future do those living in Bengal intend for their children? These are two of the many questions that confront us today, following the state terrorism at Singur and Nandigram.

On 18 December, 2006, Tapasi Malik went out, before it got light, to defecate in a field close to her house at Singur. Girls her age have to because the state government has failed to cash in on the centrally-sponsored Nirmal Gram (Clean Village) Project which funds toilets in poor homes. Tapasi was seized by the hands and legs, gagged, and repeatedly raped. She was lifted to a fireplace and thrust into it – headfirst. Well, my description of her death by fire is imaginary but, you can see, the reality must have been as grim, if not grimmer. However, contemporary Bengal failed to sense the searing pain Tapasi had been through – till she died. We in Bengal failed to burst into the kind of rage that the CPI-M takes seriously. And Nandigram happened, as a result!

Dr Sarmistha Roy, who has worked with medical teams at Nandigram, says the women in particular had been shot at the genitalia. A cadre, reported Medha Patkar to the Governor, pressed a rod into a woman’s vagina. Her uterus ruptured. Another woman, Kabita Das (35), was pinned between two sticks, and gang raped. Her husband tried to rescue her, but forced to watch on instead, since the cadres had threatened to dash their six-month-old baby to the ground and stamp it underfoot. The Statesman reported (21 March) that Sahadeb Pramanick (30), a CPI-M cadre from Gangra, was caught on 20 March while sneaking into Sonachura. He admitted to having raped two women, including a 13-year-old, on 14 March. It is also widely reported that police had opened fire near a bridge on March 14, virtually helping the CPI-M cadres to shepherd 17 girls into a deserted house owned by Shankar Samanta, a CPI-M leader. The CBI officials later found bits and pieces of women’s undergarments there, stained with blood. “Villagers had heard women’s shrieks from that house, which the cadres guarded.”

Led by Ganamukti Parishad, this writer visited Tamluk Hospital where he met a farmer’s wife in her twenties. Seeing a man in his mid-seventies, she confided that she was gang raped in the presence of policemen, the cadres tore off her blouse, and bit off her nipples. One of the women she knew had a part of her cheek bitten off. I urged the camera crew of a Bengali TV news channel, shooting around, to record her experience. But she didn’t breathe a word of what she had unburdened to me. I later heard Dola Sen reporting, at the instance of Mamata Banerjee, to Governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi that the number of women thus maimed ran into hundreds.

The whole truth, though, will never be out with the CPI-M government, headed by Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, in place. And Biman Bose expects people to “forget about Nandigram very soon”. Our insensitivity to Tapasi’s death shows that he might well be right.

Reportedly again, when cadres and police together acting in tandem went on the rampage at Nandigram, a child was seen falling to a cadre’s bullet. A woman rushed to him. They beat her with truncheons. She fled. The cadres beheaded the child, dead or half dead, for the ease of transportation – or for the fun of it. Some they buried and covered with slabs of concrete. They disembowelled the rest, so that the corpses wouldn’t float, stuffed the severed heads and torsos into sacks, drove off in truckloads, and flung them into the canals. Those who ended up in the hospitals had bullets in their heads, stomachs, chests and so on, which proves that the cadres had shot to kill them. The Dainik Statesman has since published photographs of a cadre in police uniform thrashing a villager. A local shop, called Sunny Tailors, sewed the uniforms.

The whole operation was a blitzkrieg – masterminded by Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee and Nirupam Sen – with Laksman Seth, Benoy Konar, Biman Bose and the rest of the party providing logistic support at various levels. Much as Buddhadeb owns up his “constitutional responsibility”, he pleads innocence. Kshiti Goswami, RSP leader, said on TV Buddha had two faces – one of them was a mask. Prasad Ranjan Ray, state home secretary, commented: “We had mobilised forces on the basis of Intelligence reports… of course in the full knowledge of the chief minister.” Unsurprisingly, the most preferred charge against Buddha is that he is a “habitual liar”, a “confirmed liar”.

The Dainik Statesman reports (10 March) that at a meeting of 14 political leaders and police, the District Magistrate of East Midnapore announced that “any resistance to the repair of the bridges and roads at Nandigram would be dealt with according to the law of the land”. On 13 March in another meeting held at the house of Sambhu Maiti (CPI-M), police and cadres together decided on the plan of action for the capture of Sonachura and Nandigram. They fabricated fake number plates for the cars in which to carry off dead bodies, the caps the cadres and their leaders would put on – down to the last detail.

Another report says the CBI found at the Jononi Brickfield, where the cadres had encamped, buntings, bulletins and leaflets of various CPI-M outfits, six police helmets, a Chinese revolver, 500 bullets, 14 country-made firearms, nine modern rifles and two binoculars.

Now given the size of the village, and the time (two to three hours) taken to complete the operation, the whole village, including children, must have witnessed the arson, rape and murder in action. What is to become of them – particularly the children? Small wonder, Bengal’s society today teems with arsonists, rapists and supari killers.

Dr Tapash Bhattacharjee, who frequently visits Nandigram with medical help, says living as they do under the depressing prospect of a perpetual threat of CPI-M attacks, the young men there demand “weapons rather than medicines”. The fear is not baseless, if you keep in mind Benoy Konar’s warning that only the first two of the “five-act play” are over.

Actually the CPI(M)-run state government is the pus focus of a deep social abscess that has festered over the past 30 years. Its brand of politics is an unremitting evil. It splits the entire society into us and them: those who take dictates of Alimuddin Street are us – the rest them. When the farmers of Nandigram, including their cadres, disobeyed the party, Benoy Konar threatened to knock hell out of them (life hell kore debo). Konar, of Sainbari notoriety, in which a young Sain was hacked to death before his mother, had earlier warned that, should Mahasveta Devi, Medha Patkar or Mamata Banerjee dare to visit Nandigram, the women of his party would show their bottoms (pachha). And he was as good as his word. He wouldn’t care if what he said had demeaned Indian womanhood, not to speak of that of his own party. So the villagers of Singur and Nandigram had to pay the price with arson, rape and murder. If the CPI-M has its way, the rest of India will have to in the not too distant future.

(The author is former member, West Bengal Education Commission)