Nandigram has stood up

March 30, 2007

By Saroj Giri

Everytime in India, large numbers of people, as in Kalingangar, Singur and Nandigram today, stood in a direct and antagonistic relation to capital and the state, a middle class ideology of alternative plans and people’s plans has not just acted to limit the initiative and political character of the movement to the ‘enlightened interests’ of the urban radical intelligentsia but, as a consequence, capital has instead ultimately gone ahead with its own original plans without even any kind of green restructuring. And this happened since the problem is always identified at the level of a particular technology or system of production (industrial modernisation) and not in terms of social relations, not in terms of class and power relations.

The suggested way out is then not the overthrowing of the existing class, social relations, relations of power, but a new mode of technology, a new way of, as they say, ‘relating to nature’. The question of who will control this new way of relating to nature, who and which class will be in power, the fact that the proposed new, alternative people’s plan will also be part of the regime of capital is not raised. Hence the middle class debate on displacement and rehabilitation, and people’s plans ultimately ends up justifying, providing the rationale for a possible restructuring of capital: worse, when such middle class initiatives take the form of a social movement it ends up rallying huge masses of people in the interests of capital. However we have not seen anything like this really take place in our country and this is not due to the radical character of such a social movement but since capital in India is so arrogant and powerful today that, given the extremely favourable class and political balance of forces, it does not, on this account, feel the need to restructure itself. This means that post-Narmada Bachao Andolan, the radical urban middle class is redundant, no longer needed and retrenched by capital.

This, however, has opened the space for a direct and antagonistic fight between capital and the state on one side and the people on the other. Nandigram and before this Kalinganagar represent this new juncture in the relationship between capital and the different social sections and classes. Reports from Nandigram seem to suggest that people are not just fighting to keep their land and their present means of livelihoodbut they are also destroying the relations of power that tied them to capital and the state: the CPIM after all is not exaggerating when it says Nandigram was beyond the reach of the law. Now the problem for the state is not just the setting up of the industrial plant there but of first establishing this relationship, of ending the ‘liberated’ status of Nandigram.

In the absence of any middle class radicals ‘from outside’ in the movement (for example, Medha Patkar also seems to be no more than a concerned visitor there) and the isolation of the local MP who happens to belong to the CPM, Nandigram is today unrepresentable. Different political forces willing to represent Nandigram are making their rounds to end its unrepresentability and put it in some relationship with one or the other sector of capital and the state so that while the land acquisition would not take place and the proposed plant would not come up there, it should not become another Maoist ‘hotbed’. It has therefore triggered off a clear polarisation in the Indian polity today between capital and broad masses of the people. And this polarisation is clear and the contradiction sharp since except for the CPM the rest of the left and social movements who are broadly siding with affected people are however not in there among the masses fighting the brutal might of capital and the state in both Nandigram and Kalinganagar: they are outside lamenting at the violence and ‘loss of life’ and busy dissociating themselves from the CPIM. The Maoists are of course a different story.

History

In perhaps the most obscene instance of the internalisation of dissent, a West Bengal minister recently claimed that the ongoing industrialisation of the state through SEZs seeks to undermine Fukuyama’s thesis of the end of history. While this claim is ridiculously bogus, its obverse is strikingly true for some voices opposing the SEZs: don’t large sections of social movements believe that there is no possibility of large systemic transformation and most such attempts at revolutionary transformation end up in one or the other form of totalitarianism. History has ended and we need to work towards bettering conditions under some form of a benign, reformed capitalism. In the CPIM and the social movements we therefore have two forces: one speaking in the name of the onward march of History and the other opposing precisely the rationality of such a History which only tramples peoples’ lives and autonomous ways of life. If one is speaking in the name of History, a History which is objectively given from before, the other is opposing what happens in the name of History, History as a ruse to justify power.

Both positions are, however, complicit in exonerating itself from History as such, from the making of History. In treating History as identical to the depredations of capital or as merely an ideological construct used to legitimise certain regimes of power, both positions exclude the possibility of people as the makers of history. This is the possibility opened up by Nandigram which refused to submit to the dictates of capital nor to any kind of ‘pro-people’ representation or bargaining for the right kind of technology or rehabilitation package. Nandigram did not just reject the setting up of the plant but also freed itself, at least temporarily, from the relations of dominance and subjugation that tied it up with various sectors of capital and its representatives. Thus they have actually displayed the energy and creativity of making history and have actually disproved the thesis of the end of history. Again here Nandigram’s convergence with the Maoists cannot be underestimated.

The convergence of the positions of the CPIM and of the urban intelligentsia-led social movements, therefore, cannot be underestimated. Their refusal to view people as the makers of their own history comes out very clearly also in the debate on the question of the impact of industrial plants in the concerned areas. In its broad essentials the CPIM argues that industrialisation will create much needed employment in the state while the social movement position is that it will lead to displacement and the destruction of the means of livelihood. Now this is in many senses a sterile debate since there is no basic difference between them. Both the positions view the problem in terms of what impact the new technology or plant has on the people in the region so that each tells only half the story: for isn’t it true that both displacement and the creation of jobs would take place once the plants come up so that, within this framework, what position one takes now depends on a kind of cost-benefit analysis of whether the given employment generation justifies the displacement of people. Add to this the entire issue of rehabilitation package and other economic benefits to thedisplaced and then the entire issue turns on narrow economic benefits, compensation and relief packages. What is overlooked in this framework, is that regardless of whether people, in narrow economic terms, get a good or a bad deal, they are already in a relationship of dependence with capital and hence are regarded as merely victims of modernity.

The problem is that formulating the problem in terms of the impact of the industrial plant on the people or the region completely overlooks the fact that the setting up of these plants and industrial units are the expression of the relationship in which the people and the area stands to those who wield power both within that area and outside. The proposed plant or the technology to be used and the fact of displacement are an expression of the social relations that exist both in Nandigram and in society as a whole. Capitalist or feudal social relations existed in Nandigram before the present attempts at land acquisition and it is precisely since it was already enmeshed in such relations that capital and the state attempted to set up an industry there.

Now in most cases of the movement against displacement from industrial projects, social movements have failed to challenge these oppressive social relations since they do not view displacement/rehabilitation as a reflection/symptom of these relations, of the particular form of society. The coming up of the industrial plant is viewed as something coming from outside, which will, for social movements, lead to displacement and loss of livelihood and, for the CPIM, lead to much need employment generation in the state. It is true that the technology, the capital equipment etc come from outside the village or perhaps from even outside the country but that itself is not the problem. The problem is that it usually comes as a further intensification of the oppressive social relations that exist in Nandigram or in the country as a whole: that Nandigram is in the chain of capitalist and feudal exchange and production, whose political form is provided by its representation in Parliament.

Nandigram today has rebelled against these oppressive relations and have refused to be represented in the political processes of Indian democracy. The events there so far testify that they are not just against the industrial plant or for a better rehabilitation package but against the very power relations that seek to represent them in any form, including any mediation by social movement or NGOs. Further, it also forecloses radical middle class debates on big dam versus small dam, nature-friendly technology versus nature-destructive technology that are largely forgetful that capital, particularly late capitalism, can operate as much through small dams, wind-mills or through solar energy. The essential question is who controls, who has the power to decide, what are the social relations within which the technology, the industry, the dams operate. In rejecting not just the plant or the fact of displacement but all channels of representation and rehabilitation by all factions of capital and the state, Kalinganagar and Nandigram stand in an immediate and antagonistic relationship with capital today. No wonder various leaders of the CPIM are stressing on the role of Naxalites in fomenting trouble in Nandigram.

Conclusions

Kalinganagar and now Nandigram stand out since instead of making the cost-benefit calculations through the displacement/rehabilitation, livelihood-loss/job-creation, big industry/small industry ledger, they have refused any kind of quid pro quo, any truck with any faction of capital and the state. As the state ministers bitterly complained, Nandigram has been out of the reach of the law and the state since the last two months: like the banned Maoists it has outlawed itself. It has de facto seceded providing no chance to capital and the state to show their human faces, to provide jobs, to bring in perhaps a more eco-friendly technology which will not lead to displacement, or to put in place a more robust, inclusive democratic process.

This only means that the people of Nandigram have stood up and are defending themselves. In exiting from all relations with capital and the state their lives had no value and were killed. Various concerned citizens, human rights groups, and social movement initiatives are trying to side with the victims of the massacre and have called for a judicial inquiry and have upheld their right to dissent and protest. The way however to save them is not by bringing Nandigram back into the relations of capital and the state, by revalorising them as partakers in the system, but by reversing the flow of traffic: joining the people in Nandigram in seceding from the existing social relations. Marx once said, the educators need to be educated. One can today say, the saviours need to be saved. There is a real danger today that civil society initiatives might be used by capital and the state to bring Nandigram back to the ‘democratic process’ and stop it from slipping into the hands of the Maoists. Nandigram, unmediated and unrepresented, is what needs to be defended and replicated elsewhere in the country today. This will be the first step in refuting the thesis of the end of history.

April 2nd, 2007 at 11:16 am

Saroj’s writeup, though coherent and to the point, defocuses his own correct logic by utilising borrowed notions from ideological populism (”people” etc) and post-modernism. Statements like the following, which are abundant in the note, are in fact his own non-inclination to put things in a class perspective, of which he accuses others:

“Reports from Nandigram seem to suggest that people are not just fighting to keep their land and their present means of livelihood but they are also destroying the relations of power that tied them to capital and the state”.

Who are these people? Are all of them seeking to destroy “the relations of power that tied them to capital and the state”? If we understand the West Bengal situation in a political economic and historical perspective, we will have to disaggregate this “people”, since there isn’t any homogeneous connection of “the people” to “capital and the state” today (at least not in the societies like West Bengal, which are well integrated with the mainstream Indian political economy). There must be an attempt to understand and ‘deconstruct’ the present agitations in terms of class differentiation that has perpetuated in rural Bengal under the CPIM rule. Various class interests might have integrated temporarily in the present agitations, but this is not sustainable, any Marxist intervention should start with disaggregating them and strategising on this basis. Any “people” vs capital type logic is bound to lead to the deadend of the status quoist power politics which nurtures itself by such homogenised dichotomisations, “civil society” vs the state etc.

In my view, Saroj is correct when he criticises “rights groups” “social movement” for their legalist and ‘right’-ist discourses, but he utilised similar reified notions of people, outside, secession etc. Like the former, he too thinks in terms of “middle class” “joining the people”. The only difference is that the former suffers from the middle class impotency, while Saroj seems to represent his energy from the middle class self-hatred which integrates him with the Maoists.

May 31st, 2007 at 7:12 am

Here’s an article by Sunanda Sanyal published in The Statesman (Kolkata) of 31 May 2007.

The pus focus of a deep festering abscess

by Sunanda Sanyal

What’s absolutely the limit to violence on their women that males in Bengal can bear with? What future do those living in Bengal intend for their children? These are two of the many questions that confront us today, following the state terrorism at Singur and Nandigram.

On 18 December, 2006, Tapasi Malik went out, before it got light, to defecate in a field close to her house at Singur. Girls her age have to because the state government has failed to cash in on the centrally-sponsored Nirmal Gram (Clean Village) Project which funds toilets in poor homes. Tapasi was seized by the hands and legs, gagged, and repeatedly raped. She was lifted to a fireplace and thrust into it – headfirst. Well, my description of her death by fire is imaginary but, you can see, the reality must have been as grim, if not grimmer. However, contemporary Bengal failed to sense the searing pain Tapasi had been through – till she died. We in Bengal failed to burst into the kind of rage that the CPI-M takes seriously. And Nandigram happened, as a result!

Dr Sarmistha Roy, who has worked with medical teams at Nandigram, says the women in particular had been shot at the genitalia. A cadre, reported Medha Patkar to the Governor, pressed a rod into a woman’s vagina. Her uterus ruptured. Another woman, Kabita Das (35), was pinned between two sticks, and gang raped. Her husband tried to rescue her, but forced to watch on instead, since the cadres had threatened to dash their six-month-old baby to the ground and stamp it underfoot. The Statesman reported (21 March) that Sahadeb Pramanick (30), a CPI-M cadre from Gangra, was caught on 20 March while sneaking into Sonachura. He admitted to having raped two women, including a 13-year-old, on 14 March. It is also widely reported that police had opened fire near a bridge on March 14, virtually helping the CPI-M cadres to shepherd 17 girls into a deserted house owned by Shankar Samanta, a CPI-M leader. The CBI officials later found bits and pieces of women’s undergarments there, stained with blood. “Villagers had heard women’s shrieks from that house, which the cadres guarded.”

Led by Ganamukti Parishad, this writer visited Tamluk Hospital where he met a farmer’s wife in her twenties. Seeing a man in his mid-seventies, she confided that she was gang raped in the presence of policemen, the cadres tore off her blouse, and bit off her nipples. One of the women she knew had a part of her cheek bitten off. I urged the camera crew of a Bengali TV news channel, shooting around, to record her experience. But she didn’t breathe a word of what she had unburdened to me. I later heard Dola Sen reporting, at the instance of Mamata Banerjee, to Governor Gopal Krishna Gandhi that the number of women thus maimed ran into hundreds.

The whole truth, though, will never be out with the CPI-M government, headed by Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, in place. And Biman Bose expects people to “forget about Nandigram very soon”. Our insensitivity to Tapasi’s death shows that he might well be right.

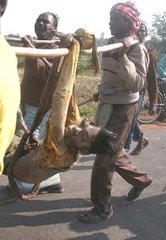

Reportedly again, when cadres and police together acting in tandem went on the rampage at Nandigram, a child was seen falling to a cadre’s bullet. A woman rushed to him. They beat her with truncheons. She fled. The cadres beheaded the child, dead or half dead, for the ease of transportation – or for the fun of it. Some they buried and covered with slabs of concrete. They disembowelled the rest, so that the corpses wouldn’t float, stuffed the severed heads and torsos into sacks, drove off in truckloads, and flung them into the canals. Those who ended up in the hospitals had bullets in their heads, stomachs, chests and so on, which proves that the cadres had shot to kill them. The Dainik Statesman has since published photographs of a cadre in police uniform thrashing a villager. A local shop, called Sunny Tailors, sewed the uniforms.

The whole operation was a blitzkrieg – masterminded by Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee and Nirupam Sen – with Laksman Seth, Benoy Konar, Biman Bose and the rest of the party providing logistic support at various levels. Much as Buddhadeb owns up his “constitutional responsibility”, he pleads innocence. Kshiti Goswami, RSP leader, said on TV Buddha had two faces – one of them was a mask. Prasad Ranjan Ray, state home secretary, commented: “We had mobilised forces on the basis of Intelligence reports… of course in the full knowledge of the chief minister.” Unsurprisingly, the most preferred charge against Buddha is that he is a “habitual liar”, a “confirmed liar”.

The Dainik Statesman reports (10 March) that at a meeting of 14 political leaders and police, the District Magistrate of East Midnapore announced that “any resistance to the repair of the bridges and roads at Nandigram would be dealt with according to the law of the land”. On 13 March in another meeting held at the house of Sambhu Maiti (CPI-M), police and cadres together decided on the plan of action for the capture of Sonachura and Nandigram. They fabricated fake number plates for the cars in which to carry off dead bodies, the caps the cadres and their leaders would put on – down to the last detail.

Another report says the CBI found at the Jononi Brickfield, where the cadres had encamped, buntings, bulletins and leaflets of various CPI-M outfits, six police helmets, a Chinese revolver, 500 bullets, 14 country-made firearms, nine modern rifles and two binoculars.

Now given the size of the village, and the time (two to three hours) taken to complete the operation, the whole village, including children, must have witnessed the arson, rape and murder in action. What is to become of them – particularly the children? Small wonder, Bengal’s society today teems with arsonists, rapists and supari killers.

Dr Tapash Bhattacharjee, who frequently visits Nandigram with medical help, says living as they do under the depressing prospect of a perpetual threat of CPI-M attacks, the young men there demand “weapons rather than medicines”. The fear is not baseless, if you keep in mind Benoy Konar’s warning that only the first two of the “five-act play” are over.

Actually the CPI(M)-run state government is the pus focus of a deep social abscess that has festered over the past 30 years. Its brand of politics is an unremitting evil. It splits the entire society into us and them: those who take dictates of Alimuddin Street are us – the rest them. When the farmers of Nandigram, including their cadres, disobeyed the party, Benoy Konar threatened to knock hell out of them (life hell kore debo). Konar, of Sainbari notoriety, in which a young Sain was hacked to death before his mother, had earlier warned that, should Mahasveta Devi, Medha Patkar or Mamata Banerjee dare to visit Nandigram, the women of his party would show their bottoms (pachha). And he was as good as his word. He wouldn’t care if what he said had demeaned Indian womanhood, not to speak of that of his own party. So the villagers of Singur and Nandigram had to pay the price with arson, rape and murder. If the CPI-M has its way, the rest of India will have to in the not too distant future.

(The author is former member, West Bengal Education Commission)