Celebrate the Resistance

By Tanika Sarkar

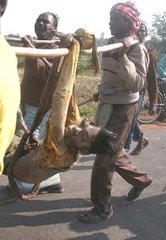

The true history of the terror at Nandigram between 14 and 16 March will probably never be disclosed in its fullness. Snippets of information that broke through the police cover, and visual fragments that could be shown on television channels have, nonetheless, brought forth an unprecedented upsurge of popular outrage all over the state, from all ranks of people. It is time to open up some old histories and structural characteristics of CPI(M) conduct in the state.

What happened in Nandigram had been rehearsed there already in early January, and at Singur, in September and December, 2006: imposition of unilateral party and corporate decisions on villagers without even informing them that their land had been acquired for corporate profit, private profit now designated as public purpose. Intimidation, especially by party cadres, violent attacks on villagers by the police and by cadres, violence that did not spare women and children. Branding of all criticism as of Trinamool, the BJP or Naxal inspiration, and hence not fit to be met with serious discussion. Slander campaigns against the Left sympathisers and against renowned social activists who balked at party-led violence. Keeping Front partners out of every crucial decision making, whether it related to land acquisition, or to organisation of violence. Singur and Nadigram, thus, raise questions about a neo liberal economics that the state party seems to have definitively embraced and which the central committee has endorsed, and about the failure of democratic processes which such policies have produced. We need to think about whether the embrace of corporate interests and surrender to corporate will can ever be managed democratically. It has not happened anywhere else in India. West Bengal proved no exception.

Land reforms in the state that the early Left Front governments initiated proved to be remarkable in their effects on peasant economy and morale, stimulating thriving small peasant agriculture and an amazing measure of peasant self-confidence and self-esteem that we saw at Singur and at Nandigram. At the same time, however, industries were allowed to die away, leaving about 50,000 dead factories and the virtual collapse of the jute industry. Beyond registration of sharecroppers and some land redistribution, no other forms of agrarian restructuring were imagined. The successful panchayat bodies were equipped with powers and functions but these very gains led to bitter conflicts and rural violence among different parties that contested the elections. While all parties were more or less implicated, especially the Trinamool, it was the CPI(M) alone which controlled the police and dominated state power.

From the mid 1990s, with the adoption of structural adjustment policies on a national scale, some new changes occurred, just as the party, battening on repeated victories, became increasingly tolerant of criticism and opposition. In the name of urban beautification, hawkers were sought to be removed from Kolkata streets, massive tracts of highly cultivated land, rich in bio-diverse resources, were taken over at New Rajarhat near the capital and handed over to corporate groups to be made over into Vedic villages, aquatic sports complexes and magnificent residential resorts for the super rich. It was the same story on both sides of the bypass that connects the capital with the airport: huge land tracts snatched from peasants and fishermen, earmarked for pleasure grounds of the rich: private hospitals, gated communities, expensive parks and entertainment centres, huge shopping malls. Government schools languished and public health was in a dismal condition at the same time: one new primary health care centre all over the state in the last ten years. While factories remained closed, half the annual funds sent under the Rural Employment Guarantee schemes were sent back untouched. We may say that the history shows no concern for promoting real industrialisation, or for public concerns, nor for employment generation. What flourished with tender government nurture had been upper middle class luxuries and corporate profits.

Another disturbing development was the cycle of misinformation. It is clear now that massive land transfers were planned without land use maps or land surveys since the early 1970s, against advice of the Geological Survey of India about the ecological damage such acquisition would lead to. Singur’s visibly multi-cropped land was designated as single cropped, misinformation abounded about the extent and purposes of land transfer and queries under the right to information were not answered. The party circulated fact sheets that were immediately disproved. Even though there was no violent movement in Singur, peaceful resistance by farmers was met with the police and cadre brutalities. It was as if the party expected that villagers would have to obey the diktat taken without any discussion with people whose land, livelihood, village, environment and culture were at stake. Singur — a village whose land was taken without information reaching the peasants prior to the event, and whose peaceful movement brought forth horrible reprisals, formed the determination of Nandigram peasants to defend their livelihood and space at any cost: in late January, some of us who visited that area, warned about an impending rural civil war.

The resistance at Nandigram has led to a few promises of concessions, only because it was fierce to the point of violence, determined, to pay any price that was needed to protect their land. At the same time, party leaders at all levels proudly declare that SEZs would happen in West Bengal. The revisions in the structure of SEZs that they suggest, however, do not involve any real protection of labour rights, no provisions for unionisation or any curbs on extra territorial powers of the companies.

What is the Left, then, in West Bengal? I would suggest that the very long and rich tradition of the Left politics and culture has survived. We need to look for them in the amazing resistance of peasants, among poor people who cling to their urban dwellings and livelihood, in the unprecedented, tumultuous expressions of solidarity with the people of Nandigram that now rock cities and towns in the state and that strengthen resistance to arbitrary state power in many other rural pockets in the state.

Source : Hardnews

No comments:

Post a Comment