Development as Poison - Rethinking the Western Model of Modernity

By Stephen A. Marglin, Walter S. Barker Professor of Economics at Harvard University.

At the beginning of Annie Hall, Woody Allen tells a story about two women returning from a vacation in New York’s Catskill Mountains. They meet a friend and immediately start complaining: “The food was terrible,” the first woman says, “I think they were trying to poison us.” The second adds, “Yes, and the portions were so small.” That is my take on development: the portions are small, and they are poisonous. This is not to make light of the very real gains that have come with development. In the past three decades, infant and child mortality have fallen by 66 percent in Indonesia and Peru, by 75 percent in Iran and Turkey, and by 80 percent in Arab oil-producing states. In most parts of the world, children not only have a greater probability of surviving into adulthood, they also have more to eat than their parents did—not to mention better access to schools and doctors and a prospect of work lives of considerably less drudgery.

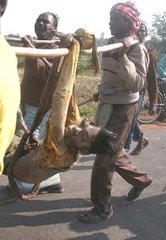

Nonetheless, for those most in need, the portions are indeed small. Malnutrition and hunger persist alongside the tremendous riches that have come with development and globalization. In South Asia almost a quarter of the population is undernourished and in sub-Saharan Africa, more than a third. The outrage of anti-globalization protestors in Seattle, Genoa, Washington, and Prague was directed against the meagerness of the portions, and rightly so.

But more disturbing than the meagerness of development’s portions is its deadliness. Whereas other critics highlight the distributional issues that compromise development, my emphasis is rather on the terms of the project itself, which involve the destruction of indigenous cultures and communities. This result is more than a side-effect of development; it is central to the underlying values and assumptions of the entire Western development enterprise.

The White Man’s Burden

Along with the technologies of production, healthcare, and education, development has spread the culture of the modern West all over the world, and thereby undermined other ways of seeing, understanding, and being. By culture I mean something more than artistic sensibility or intellectual refinement. “Culture” is used here the way anthropologists understand the term, to mean the totality of patterns of behavior and belief that characterize a specific society. Outside the modern West, culture is sustained through community, the set of connections that bind people to one another economically, socially, politically, and spiritually. Traditional communities are not simply about shared spaces, but about shared participation and experience in producing and exchanging goods and services, in governing, entertaining and mourning, and in the physical, moral, and spiritual life of the community. The culture of the modern West, which values the market as the primary organizing principle of life, undermines these traditional communities just as it has undermined community in the West itself over the last 400 years.

The West thinks it does the world a favor by exporting its culture along with the technologies that the non-Western world wants and needs. This is not a recent idea. A century ago, Rudyard Kipling, the poet laureate of British imperialism, captured this sentiment in the phrase “White Man’s burden,” which portrayed imperialism as an altruistic effort to bring the benefits of Western rule to uncivilized peoples. Political imperialism died in the wake of World War II, but cultural imperialism is still alive and well. Neither practitioners nor theorists speak today of the white man’s burden—no development expert of the 21st century hankers after clubs or golf courses that exclude local folk from membership. Expatriate development experts now work with local people, but their collaborators are themselves formed for the most part by Western culture and values and have more in common with the West than they do with their own people. Foreign advisers—along with their local collaborators—are still missionaries, missionaries for progress as the West defines the term. As our forbears saw imperialism, so we see development.

There are in fact two views of development and its relationship to culture, as seen from the vantage point of the modern West. In one, culture is only a thin veneer over a common, universal behavior based on rational calculation and maximization of individual self interest. On this view, which is probably the view of most economists, the Indian subsistence-oriented peasant is no less calculating, no less competitive, than the US commercial farmer.

There is a second approach which, far from minimizing cultural differences, emphasizes them. Cultures, implicitly or explicitly, are ranked along with income and wealth on a linear scale. As the West is richer, Western culture is more progressive, more developed. Indeed, the process of development is seen as the transformation of backward, traditional, cultural practices into modern practice, the practice of the West, the better to facilitate the growth of production and income.

What these two views share is confidence in the cultural superiority of the modern West. The first, in the guise of denying culture, attributes to other cultures Western values and practices. The second, in the guise of affirming culture, posits an inclined plane of history (to use a favorite phrase of the Indian political psychologist Ashis Nandy) along which the rest of the world is, and ought to be, struggling to catch up with us. Both agree on the need for “development.” In the first view, the Other is a miniature adult, and development means the tender nurturing by the market to form the miniature Indian or African into a full-size Westerner. In the second, the Other is a child who needs structural transformation and cultural improvement to become an adult.

Both conceptions of development make sense in the context of individual people precisely because there is an agreed-upon standard of adult behavior against which progress can be measured. Or at least there was until two decades ago when the psychologist Carol Gilligan challenged the conventional wisdom of a single standard of individual development. Gilligan’s book In A Different Voice argued that the prevailing standards of personal development were male standards. According to these standards, personal development was measured by progress from intuitive, inarticulate, cooperative, contextual, and personal modes of behavior toward rational, principled, competitive, universal, and impersonal modes of behavior, that is, from “weak” modes generally regarded as feminine and based on experience to “strong” modes regarded as masculine and based on algorithm.

Drawing from Gilligan’s study, it becomes clear that on an international level, the development of nation-states is seen the same way. What appear to be universally agreed upon guidelines to which developing societies must conform are actually impositions of Western standards through cultural imperialism. Gilligan did for the study of personal development what must be done for economic development: allowing for difference. Just as the development of individuals should be seen as the flowering of that which is special and unique within each of us—a process by which an acorn becomes an oak rather than being obliged to become a maple—so the development of peoples should be conceived as the flowering of what is special and unique within each culture. This is not to argue for a cultural relativism in which all beliefs and practices sanctioned by some culture are equally valid on a moral, aesthetic, or practical plane. But it is to reject the universality claimed by Western beliefs and practices.

Of course, some might ask what the loss of a culture here or there matters if it is the price of material progress, but there are two flaws to this argument. First, cultural destruction is not necessarily a corollary of the technologies that extend life and improve its quality. Western technology can be decoupled from the entailments of Western culture. Second, if I am wrong about this, I would ask, as Jesus does in the account of Saint Mark, “[W]hat shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” For all the material progress that the West has achieved, it has paid a high price through the weakening to the breaking point of communal ties. We in the West have much to learn, and the cultures that are being destroyed in the name of progress are perhaps the best resource we have for restoring balance to our own lives. The advantage of taking a critical stance with respect to our own culture is that we become more ready to enter into a genuine dialogue with other ways of being and believing.

The Culture of the Modern West

Culture is in the last analysis a set of assumptions, often unconsciously held, about people and how they relate to one another. The assumptions of modern Western culture can be described under five headings: individualism, self interest, the privileging of “rationality,” unlimited wants, and the rise of the moral and legal claims of the nation-state on the individual.

Individualism is the notion that society can and should be understood as a collection of autonomous individuals, that groups—with the exception of the nation-state—have no normative significance as groups; that all behavior, policy, and even ethical judgment should be reduced to their effects on individuals. All individuals play the game of life on equal terms, even if they start with different amounts of physical strength, intellectual capacity, or capital assets. The playing field is level even if the players are not equal. These individuals are taken as given in many important ways rather than as works in progress. For example, preferences are accepted as given and cover everything from views about the relative merits of different flavors of ice cream to views about the relative merits of prostitution, casual sex, sex among friends, and sex within committed relationships. In an excess of democratic zeal, the children of the 20th century have extended the notion of radical subjectivism to the whole domain of preferences: one set of “preferences” is as good as another.

Self-interest is the idea that individuals make choices to further their own benefit. There is no room here for duty, right, or obligation, and that is a good thing, too. Adam Smith’s best remembered contribution to economics, for better or worse, is the idea of a harmony that emerges from the pursuit of self-interest. It should be noted that while individualism is a prior condition for self-interest—there is no place for self-interest without the self—the converse does not hold. Individualism does not necessarily imply self-interest.

The third assumption is that one kind of knowledge is superior to others. The modern West privileges the algorithmic over the experiential, elevating knowledge that can be logically deduced from what are regarded as self-evident first principles over what is learned from intuition and authority, from touch and feel. In the stronger form of this ideology, the algorithmic is not only privileged but recognized as the sole legitimate form of knowledge. Other knowledge is mere belief, becoming legitimate only when verified by algorithmic methods.

Fourth is unlimited wants. It is human nature that we always want more than we have and that there is, consequently, never enough. The possibilities of abundance are always one step beyond our reach. Despite the enormous growth in production and consumption, we are as much in thrall to the economy as our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Most US families find one income inadequate for their needs, not only at the bottom of the distribution—where falling real wages have eroded the standard of living over the past 25 years—but also in the middle and upper ranges of the distribution. Economics, which encapsulates in stark form the assumptions of the modern West, is frequently defined as the study of the allocation of limited resources among unlimited wants.

Finally, the assumption of modern Western culture is that the nation-state is the pre-eminent social grouping and moral authority. Worn out by fratricidal wars of religion, early modern Europe moved firmly in the direction of making one’s relationship to God a private matter—a taste or preference among many. Language, shared commitments, and a defined territory would, it was hoped, be a less divisive basis for social identity than religion had proven to be.

An Economical Society

Each of these dimensions of modern Western culture is in tension with its opposite. Organic or holistic conceptions of society exist side by side with individualism. Altruism and fairness are opposed to self interest. Experiential knowledge exists, whether we recognize it or not, alongside algorithmic knowledge. Measuring who we are by what we have has been continually resisted by the small voice within that calls us to be our better selves. The modern nation-state claims, but does not receive, unconditional loyalty.

So the sway of modern Western culture is partial and incomplete even within the geographical boundaries of the West. And a good thing too, since no society organized on the principles outlined above could last five minutes, much less the 400 years that modernity has been in the ascendant. But make no mistake—modernity is the dominant culture in the West and increasingly so throughout the world. One has only to examine the assumptions that underlie contemporary economic thought—both stated and unstated—to confirm this assessment. Economics is simply the formalization of the assumptions of modern Western culture. That both teachers and students of economics accept these assumptions uncritically speaks volumes about the extent to which they hold sway.

It is not surprising then that a culture characterized in this way is a culture in which the market is the organizing principle of social life. Note my choice of words, “the market” and “social life,” not markets and economic life. Markets have been with us since time out of mind, but the market, the idea of markets as a system for organizing production and exchange, is a distinctly modern invention, which grew in tandem with the cultural assumption of the self-interested, algorithmic individual who pursues wants without limit, an individual who owes allegiance only to the nation-state.

There is no sense in trying to resolve the chicken-egg problem of which came first. Suffice it to say that we can hardly have the market without the assumptions that justify a market system—and the market system can function acceptably only when the assumptions of the modern West are widely shared. Conversely, once these assumptions are prevalent, markets appear to be a “natural” way to organize life.

Markets and Communities

If people and society were as the culture of the modern West assumes, then market and community would occupy separate ideological spaces, and would co-exist or not as people chose. However, contrary to the assumptions of individualism, the individual does not encounter society as a fully formed human being. We are constantly being shaped by our experiences, and in a society organized in terms of markets, we are formed by our experiences in the market. Markets organize not only the production and distribution of things; they also organize the production of people.

The rise of the market system is thus bound up with the loss of community. Economists do not deny this, but rather put a market friendly spin on the destruction of community: impersonal markets accomplish more efficiently what the connections of social solidarity, reciprocity, and other redistributive institutions do in the absence of markets. Take fire insurance, for example. I pay a premium of, say, US$200 per year, and if my barn burns down, the insurance company pays me US$60,000 to rebuild it. A simple market transaction replaces the more cumbersome method of gathering my neighbors for a barn-raising, as rural US communities used to do. For the economist, it is a virtue that the more efficient institution drives out the less efficient. In terms of building barns with a minimal expenditure of resources, insurance may indeed be more efficient than gathering the community each time somebody’s barn burns down. But in terms of maintaining the community, insurance is woefully lacking. Barn-raisings foster mutual interdependence: I rely on my neighbors economically—as well as in other ways—and they rely on me. Markets substitute impersonal relationships mediated by goods and services for the personal relationships of reciprocity and the like.

Why does community suffer if it is not reinforced by mutual economic dependence? Does not the relaxation of economic ties rather free up energy for other ways of connecting, as the English economist Dennis Robertson once suggested early in the 20th century? In a reflective mood toward the end of his life, Sir Dennis asked, “What does the economist economize?” His answer: “[T]hat scarce resource Love, which we know, just as well as anybody else, to be the most precious thing in the world.” By using the impersonal relationships of markets to do the work of fulfilling our material needs, we economize on our higher faculties of affection, our capacity for reciprocity and personal obligation—love, in Robertsonian shorthand—which can then be devoted to higher ends.

In the end, his protests to the contrary notwithstanding, Sir Dennis knew more about banking than about love. Robertson made the mistake of thinking that love, like a loaf of bread, gets used up as it is used. Not all goods are “private” goods like bread. There are also “public” or “collective” goods which are not consumed when used by one person. A lighthouse is the canonical example: my use of the light does not diminish its availability to you. Love is a hyper public good: it actually increases by being used and indeed may shrink to nothing if left unused for any length of time.

If love is not scarce in the way that bread is, it is not sensible to design social institutions to economize on it. On the contrary, it makes sense to design social institutions to draw out and develop the community’s stock of love. It is only when we focus on barns rather than on the people raising barns that insurance appears to be a more effective way of coping with disaster than is a community-wide barn-raising. The Amish, who are descendants of 18th century immigrants to the United States, are perhaps unique in the United States for their attention to fostering community; they forbid insurance precisely because they understand that the market relationship between an individual and the insurance company undermines the mutual dependence of the individuals that forms the basis of the community. For the Amish, barn-raisings are not exercises in nostalgia, but the cement which holds the community together.

Indeed, community cannot be viewed as just another good subject to the dynamics of market supply and demand that people can choose or not as they please, according to the same market test that applies to brands of soda or flavors of ice cream. Rather, the maintenance of community must be a collective responsibility for two reasons. The first is the so-called “free rider” problem. To return to the insurance example, my decision to purchase fire insurance rather than participate in the give and take of barn raising with my neighbors has the side effect—the “externality” in economics jargon—of lessening my involvement with the community. If I am the only one to act this way, this effect may be small with no harm done. But when all of us opt for insurance and leave caring for the community to others, there will be no others to care, and the community will disintegrate. In the case of insurance, I buy insurance because it is more convenient, and—acting in isolation—I can reasonably say to myself that my action hardly undermines the community. But when we all do so, the cement of mutual obligation is weakened to the point that it no longer supports the community.

The free rider problem is well understood by economists, and the assumption that such problems are absent is part of the standard fine print in the warranty that economists provide for the market. A second, deeper, problem cannot so easily be translated into the language of economics. The market creates more subtle externalities that include effects on beliefs, values, and behaviors—a class of externalities which are ignored in the standard framework of economics in which individual “preferences” are assumed to be unchanging. An Amishman’s decision to insure his barn undermines the mutual dependence of the Amish not only by making him less dependent on the community, but also by subverting the beliefs that sustain this dependence. For once interdependence is undermined, the community is no longer valued; the process of undermining interdependence is self-validating.

Thus, the existence of such externalities means that community survival cannot be left to the spontaneous initiatives of its members acting in accord with the individual maximizing model. Furthermore, this problem is magnified when the externalities involve feedback from actions to values, beliefs, and then to behavior. If a community is to survive, it must structure the interactions of its members to strengthen ways of being and knowing which support community. It will have to constrain the market when the market undermines community.

A Different Development

There are two lessons here. The first is that there should be mechanisms for local communities to decide, as the Amish routinely do, which innovations in organization and technology are compatible with the core values the community wishes to preserve. This does not mean the blind preservation of whatever has been sanctioned by time and the existing distribution of power. Nor does it mean an idyllic, conflict-free path to the future. But recognizing the value as well as the fragility of community would be a giant step forward in giving people a real opportunity to make their portions less meager and avoiding the poison.

The second lesson is for practitioners and theorists of development. What many Westerners see simply as liberating people from superstition, ignorance, and the oppression of tradition, is fostering values, behaviors, and beliefs that are highly problematic for our own culture. Only arrogance and a supreme failure of the imagination cause us to see them as universal rather than as the product of a particular history. Again, this is not to argue that “anything goes.” It is instead a call for sensitivity, for entering into a dialogue that involves listening instead of dictating—not so that we can better implement our own agenda, but so that we can genuinely learn that which modernity has made us forget.

Source : Harvard International Review

No comments:

Post a Comment