A Million Nandigrams

By Sunita Narain

We were standing between a massive mine and a stunning water reservoir. Local activists were explaining to me how this iron ore mine was located in the catchment of the Salaulim water reservoir, the only water source for south Goa.

Suddenly, as I clicked with my camera, we were surrounded by a jeepload of men. They said they were from the mine management and wanted us off the property. We explained that we had come on a public path and that there were no signs to indicate that we were trespassing. But they were not in a mood to listen. They snatched the keys of our jeep, picked up stones to hit us and got abusive. Before things got totally out of hand, we decided to leave.

I was completely baffled at these developments. After all, this was Goa, known for its peace and calm. This was also the place where industrialists–the Dempos, the Salgoacars, the Timblos with mineral interests–play key roles in education, in culture and in promoting the ethics of good corporate governance.

Why would they allow mining to take place next to what is clearly the most important water source for the state? Why were there no signboards with names of owners, near or around the mine? Why would state regulators allow this to happen? What was happening in this paradise to unleash this violence and simmering tension? I got my answers soon.

In the next village, Colomba, I was surrounded once again: Not by goons of a mining company, but by women of the village. We were standing on top of the hill, overlooking the village nestled between coconut and cashewnut trees. But where we were, the bulldozers, mechanised shovels and trucks were hard at work.

They were breaking the hill, shovelling its mud, dumping the rejects and then taking away the ore. The mine had just started operations, said the agitated women, but their streams were already drying up.

Understandably the villagers had just one demand: Close down the mines. I asked how permission had been given without their consent. Who were these companies and whose land were they mining? It was assumed that conditional environmental clearance had been taken to operate the mine located mostly on comunidade land–originally under local community control and only to be leased out for agriculture.

But as the concessions had been granted by the Portuguese government and later converted into leases by the Indian government, these restrictions did not seem to apply. Or, at least, did not matter.

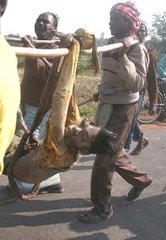

In the next village, Quinamol, the scene was more or less the same. The miners were rowdy; the villagers angry. The only difference was that the mine was older–first mined for manganese and now being excavated for iron ore. The people told me that they had complained but nobody was listening.

I learnt later–the day after my visit–that villagers had stopped a truck loading the material and beaten the driver. A case has now been registered against them. But is it only their fault?

This was the scene in all the villages we passed. What made the situation poignant, and ironical, was the fact that these villages are prosperous areas, where agricultural productivity is the basis of economic wealth. It is this well-being that is being destroyed, bit by bit. I understood then what the demand of ore from China, which had raised prices of the mineral to a new high, was doing to patterns of local economies.

It was in Vichundrem village, however, that I saw the future. Here our vehicle could not proceed up to the hill. It was blocked by a massive boulder. This was the simple but effective blockade by the village. It was their way to keep the miners out of the government forest land that surrounded their fields and provided it spring water for irrigation. The fields were gleaming green in the sun.

I had just seen a million Nandigram mutinies in the making. Where are we headed, I wonder?

No comments:

Post a Comment