Singur to Nandigram, and the shiny urban resistance">Singur to Nandigram, and the shiny urban resistance

This report deals with some of the things that I have seen, and with some of the events that I have taken part in, during the week starting on Monday 12th 2007.

If it seems too long please remember that compelling reasons make it so. The feeling of terror that Nandigram evokes is one reason. That terror is natural. But it is no reason for forgetting that terror exists elsewhere as well. It exists in Singur, for example. The report therefore begins with Singur.

March 13th.

The place is 50-minutes away from Kolkata. It is easily reached by car. One goes along a National Highway that heads north out of the city, towards places beyond Singur. Gopal Nagar is the first mouza in the district that you hit after you get off the highway. It looks prosperous. A main road runs through the middle of the village. Many ponds lie on either side of the road. There are many pukka houses. I would be happy to live in one of them. We stopped for water and tea at one such house. It belongs to the Koley family. Ratan Koley is (or was) a schoolteacher. His wife Mayarani greets us. She led the first protest against the move to locate a modern car plant in Singur. The entire family is involved in the Andolan against giving up land for industry. The women of Singur are at the forefront of the protest against land acquisition.

Medha Patkar has described Singur in a recent Daily South Asian article. I can, with one exception, confirm that description. For Haradan Bag was dead. The events that started in May 2006, events over which he had very little control, had led him to take his own life. We visited the Bag home in Beraberi Purbapara. The para is a relatively poor part of Beraberi, the mouza that lies just beyond Gopalnagar We reached the Bag household between 3 and 4 pm. The widow was prostate with grief, lying on a bed in a darkened room adjoining the veranda on which Haradan babu had consumed the pesticide that killed him. A little girl (may be her grand daughter Payel) lay fast asleep by her side. The widow’s eyes were closed. But

she was not unconscious. She kept on repeating one phrase “Amra kee korbo?” (What shall we do?), over and over. We asked her relatives about her behavior. They had to use force repeatedly to restrain her from going out of the house in the direction of what used to be her husband’s field. She would do so even at night. The relatives did not seem much troubled by her behavior. A local doctor, they said, had told them that the widow’s behavior was not at all uncommon for someone in that situation.

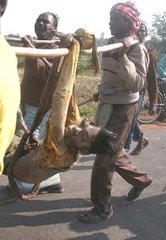

Earlier on, we had been to see the Bhui family. They had lost a young son Raj Kumar (aged 22 I believe) some months ago. Raj had been beaten severely with lathis, and I do not know what else, when he went out to attend a meeting at night. He had returned home to sleep, got up as usual, went to bathe and collapsed. He was dead by the time medical attention arrived. We attended and spoke at several Shok Sabha’s for Haradan Babu. Little white monuments were the centerpieces of all the Sabha’s. They all carried the same message “Haradan Bag, we will not forget you.” The last Sabha was held in an open field just by the side of the wall enclosing the part of Singur that the villagers no longer own.

There were plenty of uniformed, armed guards around, within the enclosure and on a watchtower. There was no communication between them and us. The Sabha, which was conducted as all such rituals usually are, needs no comment from me. But the very impressive women that I met throughout the day certainly do deserve comment. They spoke openly and vigorously about their agitation. They described how the police had assaulted them. When they reached the part where the police tore their blouses off, they mimed what had happened, holding their own hands close together in the middle of their chests, and pulling them apart violently. “What animals they are,” was all that they said then. They pointed out that some of the police wore Hawai Chappals saying “Have you ever seen a policeman on duty with hawai chappals? They were the CPM’s cadre bahini, not police.”

Wednesday March 14.

Kolkata is gripped in a large number of very quickly organized processions. People squatted on the road, in protest against the State. The State had ordered its police to kill people in Nandigram. The killings were incidental to the main objective of the operation, which was to enforce the rule of law; if

the state had been the USA, the killings would have been called “collateral damage.” There had been no rule of law in Nandigram, after the brutal fiasco called “Land acquisition, West Bengal, 2007,” had erupted there in early January. Strangely, the same State did nothing to us when we broke the law, openly, in Kolkata. I squatted along with many others in the middle of Jawaharlal Nehru Road, in the heart of the city, from before 5 pm to

around 6. 45 pm. No policeman prevented us from doing that. They even assisted us. They were very polite: “Sir, please sit a little on this side so that there is some space for cars etc. to move.” I pointed this out to Anuradha Talwar who said “Maybe, they have had enough blood for a day.” I replied, “Not so. They are the pipes for blood to flow, to the people who rule us.” Policemen, In West Bengal, obey every order they get, verbal or written, constitutional or unconstitutional. They complain vociferously - in private while they are in service, and sometimes publicly, after they retire. They are machines at best, mercenaries at worst. Take your choice.

We had marched to J L Nehru Road along two other major city streets. We started from Wellington Square, which is to the East J L Nehru Road, at 4. 30 pm. We marched down the middle of both streets. We were disrupting traffic, in a major metro and doing it during a peak traffic period. The State was silent. The people on the street watched us in silence as we marched in silence. They did not seem to mind the disruption that we caused. We carried a vivid banner showing Buddha Bhattacharya obsequiously shaking hands with a smiling Rattan Tata. Both men were on top of a mountain of human skulls. Try to imagine us doing that in Nandigram, at the same time, far away from urban India, its media and its people. Something else happened on that day. The Governor of West Bengal released an official statement on the happenings in Nandigram. He said, in part, that the happenings “have filled me with a cold horror.” I was very struck by that, and by the whole statement. Over a month ago, the Governor had promised us (meaning Samar Bagchi, Sujato Bhadra, Aditi and Sumit Choudhury and myself), when we went to Raj Bhavan to meet him (Mamata Banerjee was on hunger strike then; Medha Patkar was confined, along with several other people, to a guest house in Chandra Nagar and prevented from going anywhere near Singur) that he would do all he could. He said, very eloquently “I will saturate my constitutional role.” He had lifted both his arms as he said those words. His eyes looked very serious. The Governor had kept his word. What about the electronic media, at the national level? I watched

NDTV before going to bed. They have a “most important events” list, or something like that. The list had 8 things in it, but nothing from West Bengal. One person is killed in Gujarat and that makes the list. Many die here and the event is not recognized. I guess West Bengal has joined the country’s North Eastern states as part of India that the mainstream need not care about.

The Central Govt. certainly does not care about it. It has to rely on the support of the left. It is therefore obliged to let the warlords of the left do what they like in their own territory.

March 15th.

Another day of meetings and processions, including one by the Buddhi Jeevi people. They ask me to attend their Press Conference at the Kolkata Press Club, at 3 pm. I think, however, that Nandigram is the place to be active in, and spend some time convincing people that we need to go there, fast, if possible on March 17th. The 16th is out because there is an all Bengal 12 hour Bandh. A telephone call brings the dreadful news that lots of

people, including children were brutally murdered at the Bhanger Bera Bridge. The bridge separates Sonachura from Khejuri, and also separates the people opposed to the SEZ from the CPM’s cadres in Khejuri. I think of relaying this to the Governor, but decide not to do so till checking further. I arrive late at the Press Club. The atmosphere is extremely tense. Lots of people are there in a very small room; lots of speeches are made, by people from the theater, literary and cinema world; lots of people announce their resignations, from various Government sponsored Academies. The Press

meet is followed by a march towards the Esplanade, and a public meeting. More speeches are made there. More constructively, money is collected for the people of Nandigram. The people of Nandigram need money and medical help in vast amounts. The Presidency General Hospital in Kolkata also needs lots of blood for the wounded of Nandigram who have been shifted from Nandigram to Kolkata.

Once the meeting ends, I go to the College Square office of the National Alliance of People’s Movements hoping that they will agree to go to Nandigram. They have other plans for the 17th. But a team from Dilli consisting of B .D. Sharma, Arun Khote, D. Thankappan, Medha Patkar and other people will be coming on the evening of the 16th and going to Nandigram on a fact finding trip the next day. I am asked to accompany them, and I agree.

March 16th.

There is a 12-hour Bandh. I stay at home, getting ready to go to Nandigram early the next day.

March 17th.

A phone call from Devjit wakes me up at 4. 30 pm. I think, “Good, we are going to start early.” Not that early, alas because it is past sunrise when the van finally picks me up. We reach Nandigram by 9 pm. The drivers are very good; so is the drive. First Stop: Nandigram hospital. It is not a hospital at all but a small cluster of small, one-story buildings located on a compound just off the road into town. The wounded are in a new looking block.

A large crowd is waiting for us. They accompany us into the ward; the two guards by the gate are powerless. The wardroom is clean; there are no people on the floor as one sees in all big public hospitals in Kolkata. I speak a little, and listen a lot, to the wounded, just as all the other team members do. I shall be doing a lot of both things till midnight. The notes that I kept of the day start with A. M. She is 35, and has two girls ages 16 and 18. Her husband was away on work in Burdwan when the attack happened. Their house is in Kalicharanpur. Her husband returned late on the 16th when he heard by telephone that she was hurt. Her head hurts from a lathis blow. She was a part of the Andolan for keeping the SEZ out. The people had decided to perform a Puja to Gauranga dev, in order to avoid trouble, or to worship the Koran, with the same idea. The women and the children were put in front, facing the direction of Khejuri where the Police would come from. But it was no use. They were attacked anyway. Tear gas was used. The shells would sometimes hit people on their bodies, hard. I saw a young Muslim boy, late at night, at the Tamluk Hospital. Ho had been

hit just over his right eye. I asked him if he could see, with that eye. He whispered “No,” and clammed up. Later, we were able to get more out of him: that he was sitting for a school exam, that he was 17 years old, and that he was worried that he would not be able to complete the examination.

Consoling him was relatively easy. That was not true of other people. The old men and old women broke down very easily. They wept loudly. One old crone, bent at the waist, with a rag of a white sari around her bare body told us, when we were all standing in the hot afternoon at Sonachura bajaar,

that she had lost the only relative she had, her natni (grand daughter). When I asked for her natni’s name, she couldn’t remember it.

A recital of most of what the victims said would be a repetition of the same story line; only the details of where, and by what, they were hit would change. The women who were raped or otherwise sexually molested were something quite different. One had had alathi pushed up her uterus. Another, very young looking, said that she was 25. She spoke in whispers; no amount of sympathy from me could induce her to raise her voice, She was, really, like a small child, with a very great pain; the pain was so great that whispering was all that she could do. The brutality of the attack on her was not something that she could even remember faithfully. She said, simply, “I do not know what happened then.”

I should say something about those survivors - young and old, and male and female - who were not wounded. We met them throughout the day and the night, in theirhomes, and on the street. Young men would follow us, or crowd around us when we arrived at a teashop or wherever it was that they gathered. They would surround us in a ring, standing. The women would sit on the road. In the open, most of the talk was male talk; the women, mostly, preferred silence when theywere on the street. But there was no mistaking their determination. It had survived the long two and a half months of tense waiting. It had survived the attack when it happened. It ha survived when they hid in the jungle. It would, they said, survive the presence of the police, who they hated and the cadre who they also hated. Their message for Buddhadeba Babu was “Buddha deba ke phansi dao” (Buddhadeba should be hanged). Their message for those who led the attack that brutalized them and their community, either directly, or, like Lakshman Seth, indirectly, was different. They would kill them the moment they were able to lay hands on them. It really seems pointless to say more. But something still remains to be said, and that is about the distance separating the people of Nandigram from the State. I judge it to be vast. The State has succeeded in alienating itself from the ganasadharan as never before.

The pointedly bitter comparison with Jalianwala Bag and the British was heard over and over. “Even the British didn’t do this.”

No comments:

Post a Comment